[NOTE: this post originally appeared on Datachondria, a blog dedicated to technology, data, and modern life.]

An interesting trend with digital distribution is how cultural objects are not simply being reshaped into digital -- presumably streamlined -- versions of their content. Instead they are exploding and reforming as fairly complicated new 'clusters' of component parts.

The rebirth of cover art

Take the reappearance of liner notes for albums. During the initial stages of the MP3 revolution, liner notes and cover art seemed like the most disposable part of the package. In part that's because the scene was so unpleasantly grungy: underground, tarnished with illegitimacy, and not very easy to use. Most users wouldn't have that many songs; those that they did have might be of dubious provenance, and organized rather poorly in some system of directories -- perhaps by the P2P software by which you obtained them. Assemble a large library, and you're knocking up against the capacity of your hard drive (and the width of the pipe through which you obtained your music). You probably don't want to crowd that out with large cover art -- and even if you did, what use would it be to you?

Then came the iTunes Music Store: slick, legit, intuitive. The average user's library was likely to consist of far more songs than it might have a few years ago, and all of a sudden you need something to help you navigate, and to prompt the impulsive listen. The hard drive on your current machine was significantly larger than it was a couple of years ago. And Apple needed something to give it the stamp of legitimacy to separate it from unpleasant competitor services (legal or otherwise).

Re-enter cover art.

Liner notes are similarly making a comeback, presumably for a comparably complex matrix of reasons. They take advantage of iTunes' ability to store and display PDF files. Which is, by the way, criminally under-utilized: why doesn't the New Yorker have an iTunes store from which I can download articles for 99 cents each?

Crowdsourcing cover art

Right now, digital covers and liner notes are still soft versions of what had accompanied the physical object some years ago. But that's beginning to change.

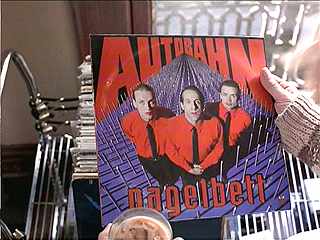

Take these fantastic covers that Logan Walters is putting together for early Wu-Tang albums:

As Walters points out, these are in the spirit of other recentdesignremixes. His rationale is very clear:

The problem was that almost all of the Wu-Tang album art was horrible (ODB's two albums being the only real exceptions) -- no offense to the original designers, but as iconic as they might be they're looking pretty dated these days.

Those are of course subjective opinions (though I'm inclined to agree, in spite of some nostalgia for Chambers and Cuban Linx). But that's exactly the point: it isn't terribly important why he wants to redesign classic Wu albums in the spirit of Blue Note; all that matters is that it helps him enjoy the material more. Looking at Walters' work, I think I might have the same reaction. I'm certainly going to try it out.

Don't judge a cover by its book

As we move away from cultural materials manifesting themselves solely in physical form, our expectations as to what exactly constitutes a 'book' or 'album' itself is obviously going to change. New reading devices will shape what is acceptable, or appropriate, in terms of raw content. The MP3 made the single the default commercial unit of music for the first time in decades.

But that doesn't mean that the ancillary materials around these works no longer have a place. Indeed, it may augment the importance of those materials. On the one hand, having communally recognized album art will help me show off my record collection when friends are over and browsing my collection via my gorgeous (and at this point theoretical) touchwall interface.

On the other hand, having album art that speaks to an aspect of the music that's particularly appealing to me -- or that shades my appreciation of it in an unexpected or unfamiliar manner -- may significantly increase my enjoyment of it.

Monetizing ancillary products

There's also a juicy financial incentive, both from the crowdsourced and top-down content creation models.

Why wouldn't artists crowdsource their album art, provide a voting interface for fans, and make alternative versions available for download from their websites? The publicity implications -- the permission marketing -- are obvious.

There is somegreatwork being done in book cover design at the moment. There a great deal of value embedded in it -- in the dialogue in which it engages with both the contents of the book and the visual culture within which it exists. Why don't publishers make book covers available for posters, T-shirts, and the like, via a one-click interface? They've already commissioned the art. Digital distribution costs are next to nothing to make the design available to third-party services like Cafe Press or Threadless. Pay a bit more to the designer for the rights to reproduce the work in different media; consumers will engage in a free marketing campaign on your behalf.

Consumers define the sum of the parts, not distributors

Cultural works are always imperfectly contained explosions of component parts -- whether they are purely physical aspects or an assemblage of expectations and impressions that consumers bring to their decision to experience a book, film, or album.

Publishers and other distributors of content need to think about how to monetize every aspect of a cultural work that has value of its own. They need to think of themselves as a 'hub' for all cultural goings-on associated with a piece of content. That's the only way to guarantee themselves a role in this new world.

Digital distribution offers a myriad of ways to re-imagine each of component parts. Cultural signifiers change so fast attach themselves with such promiscuity, and the costs to distribute pieces are so low, that book covers, pieces of music, and film posters, can float free and attach themselves to whatever uses consumers can imagine for them.

I'm sure Walter Benjamin wrote something about this. Maybe I'll go read about it -- if I like the look of one of the covers.

* Wu-Tang covers via John Mark at 33 1/3.